qubit

Overclocked quantum bit

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2007

- Messages

- 17,865 (2.86/day)

- Location

- Quantum Well UK

| System Name | Quantumville™ |

|---|---|

| Processor | Intel Core i7-2700K @ 4GHz |

| Motherboard | Asus P8Z68-V PRO/GEN3 |

| Cooling | Noctua NH-D14 |

| Memory | 16GB (2 x 8GB Corsair Vengeance Black DDR3 PC3-12800 C9 1600MHz) |

| Video Card(s) | MSI RTX 2080 SUPER Gaming X Trio |

| Storage | Samsung 850 Pro 256GB | WD Black 4TB | WD Blue 6TB |

| Display(s) | ASUS ROG Strix XG27UQR (4K, 144Hz, G-SYNC compatible) | Asus MG28UQ (4K, 60Hz, FreeSync compatible) |

| Case | Cooler Master HAF 922 |

| Audio Device(s) | Creative Sound Blaster X-Fi Fatal1ty PCIe |

| Power Supply | Corsair AX1600i |

| Mouse | Microsoft Intellimouse Pro - Black Shadow |

| Keyboard | Yes |

| Software | Windows 10 Pro 64-bit |

Boffins at Imperial College London have been researching the use of bacteria to create standard logic gates such as AND, NOR & NOT to construct a living computer with. They have actually created working prototypes that give the correct logical outputs for the corresponding inputs. The bacteria used was the common E. coli found in the gut and as typical food poisoning in a meal from a bad restaurant.

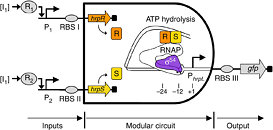

The scientists have also shown that these gates can be connected together combinatorialy, to provide complex logic functions, something that's critical to building any kind of digital circuit that is to have a useful function, such as a processor, no matter how simple. This original work, published in Nature magazine is worded in highly technical scientific language and is not easily understandable by us mere untrained mortals. However, for those that wish to dare try, click here. Here's a small sample:

What?!

Despite this complexity, as with most ideas in science, the underlying idea is actually quite simple to understand: these living bugs are put together in such a way as to make a digital logic gate. However, these logic gates don't use signals in electrical form, but instead use proteins expressed by genes as their inputs and outputs. Because these gates are modelled on the standard forms used in digital computers for the last 60+ years, they function in an equivalent way.

No word on performance compared to silicon, which one would expect to be much faster, their operating lifetime (they die?) or the possible uses of such devices in a future PC, yet. It looks like these types of living circuits are best suited for such applications as use within the body to detect things such as cancer, preventing heart attacks by cleaning arteries, plus neutralizing toxins in the environment, among a host of other possibilities. Note that just because one can't currently think of a use for this in a desktop PC, it doesn't mean that it can't happen. Many scientific discoveries and inventions didn't find their true purpose for years, with a fine example being the laser. The principle was established in 1917 by Einstein in his work 'On the Quantum Theory of Radiation', but working devices didn't appear until the late 1940s and it took decades longer until lasers were fully exploited commercially, but now they are everywhere.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

The scientists have also shown that these gates can be connected together combinatorialy, to provide complex logic functions, something that's critical to building any kind of digital circuit that is to have a useful function, such as a processor, no matter how simple. This original work, published in Nature magazine is worded in highly technical scientific language and is not easily understandable by us mere untrained mortals. However, for those that wish to dare try, click here. Here's a small sample:

The circuits were assembled using a parts-based engineering approach of quantitative characterization, modelling, followed by construction and testing. The results show that new genetic logic devices can be engineered predictably from novel native orthogonal biological control elements using quantitatively in-context characterized parts.

What?!

Despite this complexity, as with most ideas in science, the underlying idea is actually quite simple to understand: these living bugs are put together in such a way as to make a digital logic gate. However, these logic gates don't use signals in electrical form, but instead use proteins expressed by genes as their inputs and outputs. Because these gates are modelled on the standard forms used in digital computers for the last 60+ years, they function in an equivalent way.

No word on performance compared to silicon, which one would expect to be much faster, their operating lifetime (they die?) or the possible uses of such devices in a future PC, yet. It looks like these types of living circuits are best suited for such applications as use within the body to detect things such as cancer, preventing heart attacks by cleaning arteries, plus neutralizing toxins in the environment, among a host of other possibilities. Note that just because one can't currently think of a use for this in a desktop PC, it doesn't mean that it can't happen. Many scientific discoveries and inventions didn't find their true purpose for years, with a fine example being the laser. The principle was established in 1917 by Einstein in his work 'On the Quantum Theory of Radiation', but working devices didn't appear until the late 1940s and it took decades longer until lasers were fully exploited commercially, but now they are everywhere.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

nice question

nice question