- Joined

- Oct 9, 2007

- Messages

- 47,458 (7.50/day)

- Location

- Hyderabad, India

| System Name | RBMK-1000 |

|---|---|

| Processor | AMD Ryzen 7 5700G |

| Motherboard | ASUS ROG Strix B450-E Gaming |

| Cooling | DeepCool Gammax L240 V2 |

| Memory | 2x 8GB G.Skill Sniper X |

| Video Card(s) | Palit GeForce RTX 2080 SUPER GameRock |

| Storage | Western Digital Black NVMe 512GB |

| Display(s) | BenQ 1440p 60 Hz 27-inch |

| Case | Corsair Carbide 100R |

| Audio Device(s) | ASUS SupremeFX S1220A |

| Power Supply | Cooler Master MWE Gold 650W |

| Mouse | ASUS ROG Strix Impact |

| Keyboard | Gamdias Hermes E2 |

| Software | Windows 11 Pro |

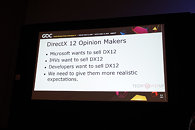

We are at the 2017 Game Developers Conference, and were invited to one of the many enlightening tech sessions, titled "Is DirectX 12 Worth it," by Jurjen Katsman, CEO of Nixxes, a company credited with several successful PC ports of console games (Rise of the Tomb Raider, Deus Ex Mankind Divided). Over the past 18 months, DirectX 12 has become the selling point to PC gamers, of everything from Windows 10 (free upgrade) to new graphics cards, and even games, with the lack of DirectX 12 support even denting the PR of certain new AAA game launches, until the developers hashed out support for the new API through patches. Game developers are asking the dev community at large to manage their expectations from DirectX 12, with the underlying point being that it isn't a silver-bullet to all the tech limitations developers have to cope with, and that to reap all its performance rewards, a proportionate amount of effort has to be put in by developers.

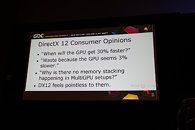

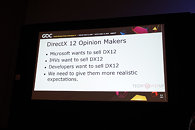

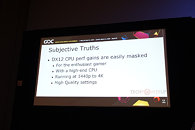

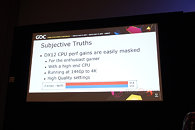

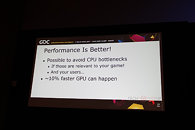

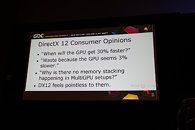

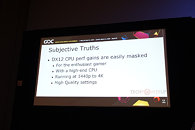

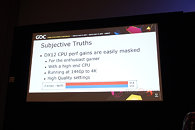

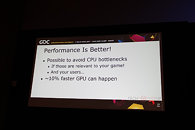

The presentation begins with the speaker talking about the disillusionment consumers have about DirectX 12, and how they're yet to see the kind of console-rivaling performance gains DirectX 12 was purported to bring. Besides lack of huge performance gains, consumers eagerly await the multi-GPU utopia that was promised to them, in which not only can you mix and match GPUs of your choice across models and brands, but also have them stack up their video memory - a theoretical possibility with by DirectX 12, but which developers argue is easier said than done, in the real world. One of the key areas where DirectX 12 is designed to improve performance is by distributing rendering overhead evenly among many CPU cores, in a multi-core CPU. For high-performance desktop users with reasonably fast CPUs, the gains are negligible. This also goes for people gaming on higher resolutions, such as 1440p and 4K Ultra HD, where the frame-rates are low, and the performance tends to be more GPU-limited.

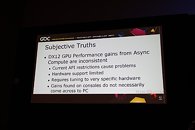

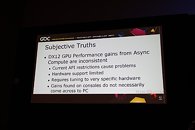

The other big feature introduced to the mainstream with DirectX 12, is asynchronous compute. There have been examples of games that take advantage of gaining more performance out of a certain brand of GPU than the other, and this is a problem, according to developers. Hardware support to async compute is limited to only the latest GPU architectures, and requires further tuning specific to the hardware. Performance gains seen on closed ecosystems such as consoles, hence, don't necessarily come over to the PC. It is therefore concluded that performance gains with async compute are inconsistent, and hence developers should manage their time on making a better game than focusing on a very specific hardware user-base.

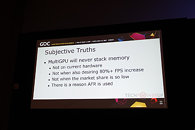

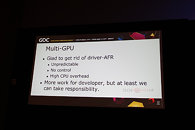

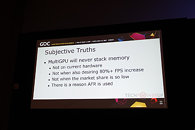

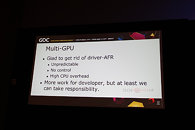

The speakers also cast aspersions on the viability of memory stacking on multi-GPU - the idea where memory of two GPUs simply add up to become one large addressable block. To begin with, the multi-GPU user-base is still far too small for developers to spend more effort than simply hashing out an AFR (alternate frame rendering) code for their games. AFR, the most common performance-improving multi-GPU method, where each GPU in a multi-GPU renders an alternative frame for the master GPU to output in sequence; requires that each GPU has a copy of the video-memory mirrored with the other GPUs. Having to fetch data from the physical memory of a neighboring GPU is a performance-costly and time-consuming process.

The idea behind new-generation "close-to-the-metal" APIs such as DirectX 12 and Vulkan, has been to make graphics drivers as less relevant to the rendering pipeline as possible. The speakers contend that the drivers are still very relevant, and instead, with the advent of the new APIs, their complexities have further gone up, in the areas of memory management, manual multi-GPU (custom, non-AFR multi-GPU implementations), the underlying tech required to enable async compute, and the various performance-enhancement tricks the various driver vendors implement to make their brand of hardware faster, which in turn can mean uncertainties for the developer in cases where the driver overrides certain techniques, just to squeeze out a little bit of extra performance.

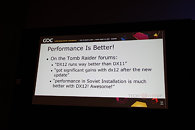

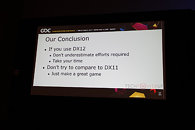

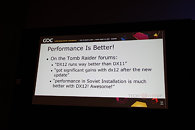

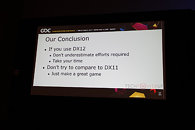

The developers revisit the question - is DirectX 12 worth it? Well, if you are willing to invest a lot of time into your DirectX 12 implementation, you could succeed, such as in case of "Rise of the Tomb Raider," in which users noticed "significant gains" with the new API (which were not trivial to achieve). They also argue that it's possible to overcome CPU bottlenecks with or without DirectX 12, if that's relevant to your game or user-base. They also concede that Async Compute is the way forward, and if not console-rivaling performance gains, it can certainly benefit the PC. They're also happy to have gotten rid of AFR multi-GPU as governed by the graphics driver, which was unpredictable and had little control (remember those pesky 400 MB driver updates just to get multi-GPU support?). The new API-governed AFR means more work for the developer, but also far greater control, which the speaker believe, will benefit the users. Another point he made is that successful porting to DirectX 12 lays a good foundation for porting to Vulkan (mostly for mobile), which uses nearly identical concepts, technologies and APIs as DX12.

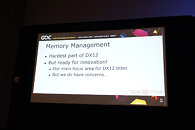

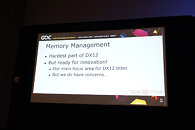

Memory management is the hardest part about DirectX 12, but the developer community is ready to embrace the innovation (such as mega-textures, tiled-resources, etc). The speakers conclude stating that DirectX 12 is hard, it can be worth the extra effort, but it may not be, either. Developers and consumers need to be realistic about what to expect from DirectX, and developers in particular to focus on making good games, rather than sacrificing their resources on becoming tech-demonstrators than on actual content.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

The presentation begins with the speaker talking about the disillusionment consumers have about DirectX 12, and how they're yet to see the kind of console-rivaling performance gains DirectX 12 was purported to bring. Besides lack of huge performance gains, consumers eagerly await the multi-GPU utopia that was promised to them, in which not only can you mix and match GPUs of your choice across models and brands, but also have them stack up their video memory - a theoretical possibility with by DirectX 12, but which developers argue is easier said than done, in the real world. One of the key areas where DirectX 12 is designed to improve performance is by distributing rendering overhead evenly among many CPU cores, in a multi-core CPU. For high-performance desktop users with reasonably fast CPUs, the gains are negligible. This also goes for people gaming on higher resolutions, such as 1440p and 4K Ultra HD, where the frame-rates are low, and the performance tends to be more GPU-limited.

The other big feature introduced to the mainstream with DirectX 12, is asynchronous compute. There have been examples of games that take advantage of gaining more performance out of a certain brand of GPU than the other, and this is a problem, according to developers. Hardware support to async compute is limited to only the latest GPU architectures, and requires further tuning specific to the hardware. Performance gains seen on closed ecosystems such as consoles, hence, don't necessarily come over to the PC. It is therefore concluded that performance gains with async compute are inconsistent, and hence developers should manage their time on making a better game than focusing on a very specific hardware user-base.

The speakers also cast aspersions on the viability of memory stacking on multi-GPU - the idea where memory of two GPUs simply add up to become one large addressable block. To begin with, the multi-GPU user-base is still far too small for developers to spend more effort than simply hashing out an AFR (alternate frame rendering) code for their games. AFR, the most common performance-improving multi-GPU method, where each GPU in a multi-GPU renders an alternative frame for the master GPU to output in sequence; requires that each GPU has a copy of the video-memory mirrored with the other GPUs. Having to fetch data from the physical memory of a neighboring GPU is a performance-costly and time-consuming process.

The idea behind new-generation "close-to-the-metal" APIs such as DirectX 12 and Vulkan, has been to make graphics drivers as less relevant to the rendering pipeline as possible. The speakers contend that the drivers are still very relevant, and instead, with the advent of the new APIs, their complexities have further gone up, in the areas of memory management, manual multi-GPU (custom, non-AFR multi-GPU implementations), the underlying tech required to enable async compute, and the various performance-enhancement tricks the various driver vendors implement to make their brand of hardware faster, which in turn can mean uncertainties for the developer in cases where the driver overrides certain techniques, just to squeeze out a little bit of extra performance.

The developers revisit the question - is DirectX 12 worth it? Well, if you are willing to invest a lot of time into your DirectX 12 implementation, you could succeed, such as in case of "Rise of the Tomb Raider," in which users noticed "significant gains" with the new API (which were not trivial to achieve). They also argue that it's possible to overcome CPU bottlenecks with or without DirectX 12, if that's relevant to your game or user-base. They also concede that Async Compute is the way forward, and if not console-rivaling performance gains, it can certainly benefit the PC. They're also happy to have gotten rid of AFR multi-GPU as governed by the graphics driver, which was unpredictable and had little control (remember those pesky 400 MB driver updates just to get multi-GPU support?). The new API-governed AFR means more work for the developer, but also far greater control, which the speaker believe, will benefit the users. Another point he made is that successful porting to DirectX 12 lays a good foundation for porting to Vulkan (mostly for mobile), which uses nearly identical concepts, technologies and APIs as DX12.

Memory management is the hardest part about DirectX 12, but the developer community is ready to embrace the innovation (such as mega-textures, tiled-resources, etc). The speakers conclude stating that DirectX 12 is hard, it can be worth the extra effort, but it may not be, either. Developers and consumers need to be realistic about what to expect from DirectX, and developers in particular to focus on making good games, rather than sacrificing their resources on becoming tech-demonstrators than on actual content.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

Last edited by a moderator:

)

)