Raevenlord

News Editor

- Joined

- Aug 12, 2016

- Messages

- 3,755 (1.16/day)

- Location

- Portugal

| System Name | The Ryzening |

|---|---|

| Processor | AMD Ryzen 9 5900X |

| Motherboard | MSI X570 MAG TOMAHAWK |

| Cooling | Lian Li Galahad 360mm AIO |

| Memory | 32 GB G.Skill Trident Z F4-3733 (4x 8 GB) |

| Video Card(s) | Gigabyte RTX 3070 Ti |

| Storage | Boot: Transcend MTE220S 2TB, Kintson A2000 1TB, Seagate Firewolf Pro 14 TB |

| Display(s) | Acer Nitro VG270UP (1440p 144 Hz IPS) |

| Case | Lian Li O11DX Dynamic White |

| Audio Device(s) | iFi Audio Zen DAC |

| Power Supply | Seasonic Focus+ 750 W |

| Mouse | Cooler Master Masterkeys Lite L |

| Keyboard | Cooler Master Masterkeys Lite L |

| Software | Windows 10 x64 |

You've heard of the Petya ransomware by now. The surge, which hit around 64 countries by June 27th, infected an estimated 12,500 computers in Ukraine alone, hitting several critical infrastructures in the country (just goes to show how vulnerable our connected systems are, really.) The number one hit country was indeed Ukraine, but the wave expanded to the Russian Federation, Poland, and eventually hit the USA (the joys of globalization, uh?) But now, some interesting details on the purported ransomware attack have come to light, which shed some mystery over the entire endeavor. Could it be that Petya (which is actually being referred to as NotPetya/SortaPetya/Petna as well, for your reference, since it mostly masquerades as that well-known ransomware) wasn't really a ransomware attack?

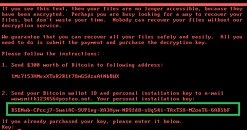

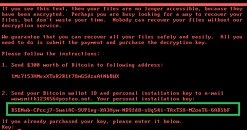

Let's get this clear: there was a ransomware edge to this attack, of that there is no doubt. Petya worked as most ransomwares do: encrypting a given computer's files and NTFS libraries, forcing devices to reboot, and then displaying ransom demands, with instructions detailing how to pay for the liberation of the encrypted files. However, the way in which this was done is unusual, to say the least. There are a number of ways to go about demanding ransoms; wallet addresses for cryptocurrency are the most common. What is strange in this whole affair is that the would-be perpetrators of the attack used a public email address (provided by Posteo) for their ransom demands. Naturally, Posteo closed down the e-mail account as soon as it became clear their service was being used for nefarious purposes (whether or not this was the best course of action is debatable.) But this closed the sole means of communication between the perpetrators and their victims, which now had no way to contact them towards obtaining the wallet address where they were supposed to send funds, nor receiving eventual decryption keys. Now I don't know about you, but a group capable of forking a variant of a GoldenEye ransomware and leading it to infect thousands of computers and critical infrastructure didn't consider this might happen? I don't buy it.

An information security researcher that goes by the pseudonymous "the grugq" had this to say regarding Petya/NotPetya:

"Although the worm is camouflaged to look like the infamous Petya ransomware, it has an extremely poor payment pipeline. There is a single hardcoded BTC wallet and the instructions require sending an email with a large amount of complex strings (something that a novice computer victim is unlikely to get right.) If this well engineered and highly crafted worm was meant to generate revenue, this payment pipeline was possibly the worst of all options (short of "send a personal cheque to: Petya Payments, PO Box …"). The superficial resemblance to Petya is only skin deep. Although there is significant code sharing, the real Petya was a criminal enterprise for making money. This is definitely not designed to make money. This is designed to spread fast and cause damage, with a plausibly deniable cover of "ransomware."

So, basically coders competent enough for such a fork chose the worst possible payment channel available, despite numerous cases of actual ransomware "done right", if you'll allow me. Kaspersky labs went on with an update, where Anton Ivanov and Orkhan Mamedov confirmed that the attackers "cannot decrypt victims' disk, even if a payment was made." They go on saying that "This supports the theory that this malware campaign was not designed as a ransomware attack for financial gain. Instead, it appears it was designed as a wiper pretending to be ransomware. (...)

Another analyst from Comae Technologies came to the same conclusion regarding the attack, saying that "Ransomware and hackers are becoming the scapegoats of nation state attackers. Petya is a wiper, not a ransomware."

The fact that this particular version of the Petya ransomware had its patient zero in the Me-doc software, which is one of only two approved accounting software in Ukraine and the most widely used in Ukrainian companies and government, means that "an attack launched from MeDoc would hit not only Ukraine's government but many foreign investors and companies." The Me-doc infection vector was later confirmed by the Ukrainian police's cyber-security department.

It seems this ransomware attack was nothing more than a wiper attack, disguised as ransomware, with the sole purpose of infecting as much of Ukraine's infrastructure and essential services as possible, while attempting infection of businesses connected with the country (which is likely why the infection spread through those at least 64 countries we mentioned at the beginning of this piece.)

It would appear a vaccine of sorts was in the meantime found towards thwarting this version of Petya, preventing it from running its installation algorithm on your computer (perhaps a fail-safe from the perpetrators so as to avoid their own machines from being infected with the malware?) Researchers from Serper advanced (and this was later confirmed by other independent security research agencies) that Petya looks for a particular file on systems, aborting its installation if it finds said file. To make yourself immune to the Petya installation, according to the researchers (and I have to put a little disclaimer here that other versions of the software could perfectly change the target lookup file), you should "create a file called perfc in the C:\Windows folder and make it read only. A batch file is available, created by Bleeping Computer's owner Lawrence Abrams.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

Let's get this clear: there was a ransomware edge to this attack, of that there is no doubt. Petya worked as most ransomwares do: encrypting a given computer's files and NTFS libraries, forcing devices to reboot, and then displaying ransom demands, with instructions detailing how to pay for the liberation of the encrypted files. However, the way in which this was done is unusual, to say the least. There are a number of ways to go about demanding ransoms; wallet addresses for cryptocurrency are the most common. What is strange in this whole affair is that the would-be perpetrators of the attack used a public email address (provided by Posteo) for their ransom demands. Naturally, Posteo closed down the e-mail account as soon as it became clear their service was being used for nefarious purposes (whether or not this was the best course of action is debatable.) But this closed the sole means of communication between the perpetrators and their victims, which now had no way to contact them towards obtaining the wallet address where they were supposed to send funds, nor receiving eventual decryption keys. Now I don't know about you, but a group capable of forking a variant of a GoldenEye ransomware and leading it to infect thousands of computers and critical infrastructure didn't consider this might happen? I don't buy it.

An information security researcher that goes by the pseudonymous "the grugq" had this to say regarding Petya/NotPetya:

"Although the worm is camouflaged to look like the infamous Petya ransomware, it has an extremely poor payment pipeline. There is a single hardcoded BTC wallet and the instructions require sending an email with a large amount of complex strings (something that a novice computer victim is unlikely to get right.) If this well engineered and highly crafted worm was meant to generate revenue, this payment pipeline was possibly the worst of all options (short of "send a personal cheque to: Petya Payments, PO Box …"). The superficial resemblance to Petya is only skin deep. Although there is significant code sharing, the real Petya was a criminal enterprise for making money. This is definitely not designed to make money. This is designed to spread fast and cause damage, with a plausibly deniable cover of "ransomware."

So, basically coders competent enough for such a fork chose the worst possible payment channel available, despite numerous cases of actual ransomware "done right", if you'll allow me. Kaspersky labs went on with an update, where Anton Ivanov and Orkhan Mamedov confirmed that the attackers "cannot decrypt victims' disk, even if a payment was made." They go on saying that "This supports the theory that this malware campaign was not designed as a ransomware attack for financial gain. Instead, it appears it was designed as a wiper pretending to be ransomware. (...)

Another analyst from Comae Technologies came to the same conclusion regarding the attack, saying that "Ransomware and hackers are becoming the scapegoats of nation state attackers. Petya is a wiper, not a ransomware."

The fact that this particular version of the Petya ransomware had its patient zero in the Me-doc software, which is one of only two approved accounting software in Ukraine and the most widely used in Ukrainian companies and government, means that "an attack launched from MeDoc would hit not only Ukraine's government but many foreign investors and companies." The Me-doc infection vector was later confirmed by the Ukrainian police's cyber-security department.

It seems this ransomware attack was nothing more than a wiper attack, disguised as ransomware, with the sole purpose of infecting as much of Ukraine's infrastructure and essential services as possible, while attempting infection of businesses connected with the country (which is likely why the infection spread through those at least 64 countries we mentioned at the beginning of this piece.)

It would appear a vaccine of sorts was in the meantime found towards thwarting this version of Petya, preventing it from running its installation algorithm on your computer (perhaps a fail-safe from the perpetrators so as to avoid their own machines from being infected with the malware?) Researchers from Serper advanced (and this was later confirmed by other independent security research agencies) that Petya looks for a particular file on systems, aborting its installation if it finds said file. To make yourself immune to the Petya installation, according to the researchers (and I have to put a little disclaimer here that other versions of the software could perfectly change the target lookup file), you should "create a file called perfc in the C:\Windows folder and make it read only. A batch file is available, created by Bleeping Computer's owner Lawrence Abrams.

View at TechPowerUp Main Site

Last edited: