8

8

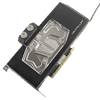

Watercool Heatkiller V RTX 3080/3090 + eBC Backplate Review

Thermal Performance »Liquid Flow Restriction

To make things simpler, I have decided to use a CORSAIR Hydro XD5 pump/reservoir combo unit rather than a discrete pump and reservoir. The pump is powered by a direct SATA connection to a CORSAIR HX750 PSU and controlled by an Aquacomputer Aquaero 6 XT. There is a previously calibrated in-line flow meter and Dwyer 490 Series 1 wet-wet manometer to measure the pressure drop of the component being tested—in this case that of each radiator. Every component is connected to the manometer by the way of 13/16 mm tubing, compression fittings, and two T-fittings.

As of the time of this review, I have tested seven entries in total. Unless specifically mentioned, every one was tested with an accompanying backplate. As that was the majority of them as of round one, this will not change in the future, either. Those without a backplate specifically named in the plots come with one included with the block and not as an optional purchase. All seven have now had dedicated reviews, and more are being tested right now. So keep in mind that the highlighted entry is for the Watercool Heatkiller GPU block and backplate combination.

Of course, I would say that a backplate generally does not matter as far as liquid-flow restriction goes, but this generation has been nuts. Not only have we had some very interesting water blocks come out for the NVIDIA Founders Edition cards, but the hot VRAM on the back of the RTX 3090 PCB has caused enough interest for a couple of companies to offer active backplates for the first time. This is why there is a separate entry where an active backplate is added.

I do not expect much to change with the copper cold plate, though there may perhaps be a slightly lower pressure drop owing to the nickel-plating no longer taking up some room in the microchannels. As such, the results here will be indicative of the entire Heatkiller V range for the RTX 3080/3090 reference PCB blocks, and we see it is slightly more restrictive than average owing to the more complex cooling engine and higher number of fins.

Dec 23rd, 2024 14:54 EST

change timezone

Latest GPU Drivers

New Forum Posts

- nvidia gpu market share takes over 90% in Q4 2024 (Get's closer to full monopoly) (339)

- Ryzen Owners Zen Garden (7611)

- Where I can buy the Samsung 35E 18650 3500mAh 8A -Protected Button Top Batteries. (26)

- AAF Optimus Modded Driver For Windows 10 & Windows 11 - Only for Realtek HDAUDIO Chips (217)

- Best time to sell your used 4090s is now. (139)

- Folding Pie and Milestones!! (9284)

- [Test Build] Fix for installation not working with Nv App (14)

- Issues with drivers 566.36 and NVCleanstall v1.17 (34)

- Rattle sound on 7800XT (30)

- Question HDD + case + eject windows (41)

Popular Reviews

- Arrow Lake Retested with Latest 24H2 Updates and 0x114 Microcode

- Team Group T-FORCE Dark AirFlow I SSD Cooler Review

- Intel Arc B580 Review - Excellent Value

- DUNU DK3001BD In-Ear Monitors Review - Brain Dance Time!

- AMD Ryzen 7 9800X3D Review - The Best Gaming Processor

- Montech MKey PRO Wireless Mechanical Keyboard Review

- ASRock Arc B580 Steel Legend Review

- Dangbei Atom ALPD Laser Projector Review

- FiiO BTR17 Portable Bluetooth DAC and Headphones Amplifier Review

- Upcoming Hardware Launches 2024 (Updated Nov 2024)

Controversial News Posts

- Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger Retires, Company Appoints two Interim co-CEOs (217)

- AMD Radeon RX 8800 XT RDNA 4 Enters Mass-production This Month: Rumor (215)

- 32 GB NVIDIA RTX 5090 To Lead the Charge As 5060 Ti Gets 16 GB Upgrade and 5060 Still Stuck With Last-Gen VRAM Spec (167)

- NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5070 Ti Leak Tips More VRAM, Cores, and Power Draw (160)

- AMD Radeon RX 8800 XT Reportedly Features 220 W TDP, RDNA 4 Efficiency (123)

- NVIDIA Blackwell RTX and AI Features Leaked by Inno3D (90)

- Intel 18A Process Node Clocks an Abysmal 10% Yield: Report (90)

- AMD Radeon "RX 8800 XT" is Actually the RX 9070 XT? (86)