Sunday, January 16th 2022

Intel "Raptor Lake" Rumored to Feature Massive Cache Size Increases

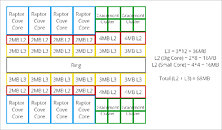

Large on-die caches are expected to be a major contributor to IPC and gaming performance. The upcoming AMD Ryzen 7 5800X3D processor triples its on-die last-level cache using the 3D Vertical Cache technology, to level up to Intel's "Alder Lake-S" processors in gaming, while using the existing "Zen 3" IP. Intel realizes this, and is planning a massive increase in on-die cache sizes, although spread across the cache hierarchy. The next-generation "Raptor Lake-S" desktop processor the company plans to launch in the second half of 2022 is rumored to feature 68 MB of "total cache" (that's AMD lingo for L2 + L3 caches), according to a highly plausible theory by PC enthusiast OneRaichu on Twitter, and illustrated by Olrak29_.

The "Raptor Lake-S" silicon is expected to feature eight "Raptor Cove" P-cores, and four "Gracemont" E-core clusters (each cluster amounts to four cores). The "Raptor Cove" core is expected to feature 2 MB of dedicated L2 cache, an increase over the 1.25 MB L2 cache per "Golden Cove" P-core of "Alder Lake-S." In a "Gracemont" E-core cluster, four CPU cores share an L2 cache. Intel is looking to double this E-core cluster L2 cache size from 2 MB per cluster on "Alder Lake," to 4 MB per cluster. The shared L3 cache increases from 30 MB on "Alder Lake-S" (C0 silicon), to 36 MB on "Raptor Lake-S." The L2 + L3 caches hence add up to 68 MB. All eyes are now on "Zen 4," and whether AMD gives the L2 caches an increase from the 512 KB per-core size that it's consistently maintained since the first "Zen."

Sources:

OneRaichu (Twitter), Olrack (Twitter), HotHardware

The "Raptor Lake-S" silicon is expected to feature eight "Raptor Cove" P-cores, and four "Gracemont" E-core clusters (each cluster amounts to four cores). The "Raptor Cove" core is expected to feature 2 MB of dedicated L2 cache, an increase over the 1.25 MB L2 cache per "Golden Cove" P-core of "Alder Lake-S." In a "Gracemont" E-core cluster, four CPU cores share an L2 cache. Intel is looking to double this E-core cluster L2 cache size from 2 MB per cluster on "Alder Lake," to 4 MB per cluster. The shared L3 cache increases from 30 MB on "Alder Lake-S" (C0 silicon), to 36 MB on "Raptor Lake-S." The L2 + L3 caches hence add up to 68 MB. All eyes are now on "Zen 4," and whether AMD gives the L2 caches an increase from the 512 KB per-core size that it's consistently maintained since the first "Zen."

66 Comments on Intel "Raptor Lake" Rumored to Feature Massive Cache Size Increases

- It would be great if lower SKU would still keep the full 36MB L3 cache, but that do not seems to be the case.

- In this model, it really look like the L3 is for core to core communication.

- I wonder if L2 to L3 is Exclusive or if the first 2 MB of each 3MB contain the L3 cache

- I wonder how fast that L2 will be. They might need a fast L2 to feed the core, but if the latency is too high, the core might starve and they might lose a lot of cycles.

- I feel the small core might have an easier time to talk to the main core with that design if the L3 cache is fully connected.

We will have to see. it's good that both Zen 4 and Meteor Lake look promising.

Let them fight

Consumer gets better products

The total cache tells little of the relative performance of CPUs. Performance matters, not specs, especially pointless specs.Very little.

The largest changes are in the E-cores, which have little impact on most workloads. The extra L3 cache is also shared with more cores, so it's not likely to offer a substantial improvement in general. And judging by performance scaling on Xeons, having extra L3 with more cores doesn't offer a significant change.

Whether more cache adds more latency is implementation specific. In this case they are adding more blocks of L3, which at least increases latency to the banks farthest away, although small compared to RAM of course.

It's also a fab process game, cache is expensive both from a power and a die area point of view.

Also keep in mind cache latency (like RAM latency) is usually given in clock cycles. 1-2 more clock cycles can be masked by increasing the frequency accordingly (it's a bit more complicated than that, really, but that's the gist of it.)

Though tbh absolute size is usually meaningless. The cache size is tightly coupled with the underlying architecture (i.e. 2MB/core wouldn't have made a difference for Netburst), size alone doesn't tell much.

cdn.videocardz.com/1/2021/03/Intel-Raptor-Lake-VideoCardz.jpg

Even for a core with a large 2 MB L2 cache, it only makes up 32768 cache lines. And if you consider that the CPU can prefetch multiple cachelines per clock, not to mention the fact that the CPU prefetches a lot of data which is never used before eviction, even an L3 cache 10-20x this size will probably be overwritten within a few thousand clock cycles. (don't forget other threads are competing over the L3) So, if you want the code of an application to "stay in cache", you pretty much have to make sure all the (relevant) code is executed every few thousand clock cycles, otherwise other cache lines will get it evicted. Also keep in mind that data cache lines usually greatly outnumber code cache lines, so the more data the application churns through, the more often it needs to access the code cache lines for them to remain in cache. Don't forget that other threads and things like system calls will also pull other code and data into caches, competing with your application. In practice, the entire cache is usually overwritten every few microseconds, with the possible exception if some super dense code is running constantly and are running exclusively on that core.

So if you have a demanding application, it's not the entire application in cache, it's probably only the heavy algorithm you use at that moment in time, and possibly only a small part of a larger algorithm, that fits in cache at the time.

8 P-cores is enough for the moment, and based on historic trends, enough for a decade or more.

If something is truly multi-threaded the problem is IPC/Watt and IPC/die-area. There's only so much power you can pump into a motherboard socket, and only so much cooling something can handle before it becomes too difficult for mainstream consumer use. E-cores vastly outperform P-cores in terms of power efficiency and area efficiency, so it's a no-brainer to just throw more of them at heavily-threaded workloads.

Quad core CPUs were launched in 2008 and were good up until at least 2018. Arguably a 4C/8T is still decent enough today but definitely no longer in its prime.

Bring that forward and the 6+4core and above Rocket Lake model will likely last 8 to 10 year barring a massive breakthrough in IC substrate materials.