Thursday, May 18th 2017

WannaCry: Its Origins, and Why Future Attacks may be Worse

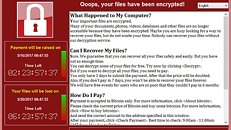

WannaCry, the Cryptographic Ransomware that encrypted entire PCs and then demanded payment via Bitcoin to unlock them, is actually not a new piece of technology. Ransomware of this type has existed nearly as long as the cryptocurrency Bitcoin has. What made headlines was the pace with which it spread and the level of damage it caused to several facilities dependent on old, seldom-updated software (Hospitals, for example). It's not a stretch to say this may be the first cyberattack directly attributable to a civilian death, though that has not been concluded yet as we are still waiting for the dust to settle. What is clear however is WHY it spread so quickly, and it's quite simple really: Many users don't have their PCs up to date.Indeed, the bug that WannaCry utilized to spread this rather old-school ransomware tech had been patched in Windows for about 2 months at the date of the outbreak. But many users were still not patched up. To be clear, this is not just hospital equipment and such that may be difficult to directly patch, but also end user PCs that simply aren't patched due to user ignorance or outright laziness. That as a cultural issue can be fixed relatively easily (and to some degree already is with the push of Windows 10 which handles this automatically for the user). But there is a more sinister twist to this story, one that indicates future outbreaks may be worse. The bug that enabled this to happen was leaked directly from the NSA, and had been known for much much longer than the patch for it has existed. In other words, this bug had been stockpiled by the US government for use in cyberwarfare, and its leak caused this attack.

Let me play you a theoretical scenario, one not so farfetched I would think. What if Microsoft had NOT had a patch ready at the time of this outbreak? What if the bug (which exists in the file sharing stack and has most Windows PC vulnerable by default) was exposed and we had to wait a couple days for a patch. What can you do to protect yourself then?

This seemingly nightmarish scenario is a good illustration of why stockpiling vulnerabilities in common software rather than reporting them is a bad practice rather than a good one. Of course, in the above situation, you could just turn your PC off until it all blows over, or turn off SMB1 file sharing in Windows (google will help you here). Or best yet, you could use a decent firewall setup that does NOT expose SMB ports to the internet (you can even block the ports in Windows Firewall, google again has the answers). But not all of us are power users. Most out there aren't, actually. A lot of users actually plug their computers directly into their modems. I know, because I've worked IT. I've seen it. And what about when someone finds a worse vulnerability, like in the TCP/IP stack? What then? Do you unplug your computer from the internet entirely? Ok, but who got infected first to tell you to do that? Someone had to take one for the team. Either way, damage has been done people.

This is why the practice of stockpiling exploits has to stop. The US government (and others, for that matter) should report exploits, not store them as cyber weapons. As weapons of war, they are as likely to hurt us in the end as our enemies, and that makes them very bad weapons in the perspective of one of the first rules of warfare; Don't hurt your own team.

Call me crazy, but that just seems like a weapon I'd rather not use. If a weapon hurts as many of your own team as your enemy or even close to that number, its time to retire that weapon. Of course, we aren't talking a literal injury or body count here, but the concept is the same. This is just a bad practice, and it needs to stop.

Let me play you a theoretical scenario, one not so farfetched I would think. What if Microsoft had NOT had a patch ready at the time of this outbreak? What if the bug (which exists in the file sharing stack and has most Windows PC vulnerable by default) was exposed and we had to wait a couple days for a patch. What can you do to protect yourself then?

This seemingly nightmarish scenario is a good illustration of why stockpiling vulnerabilities in common software rather than reporting them is a bad practice rather than a good one. Of course, in the above situation, you could just turn your PC off until it all blows over, or turn off SMB1 file sharing in Windows (google will help you here). Or best yet, you could use a decent firewall setup that does NOT expose SMB ports to the internet (you can even block the ports in Windows Firewall, google again has the answers). But not all of us are power users. Most out there aren't, actually. A lot of users actually plug their computers directly into their modems. I know, because I've worked IT. I've seen it. And what about when someone finds a worse vulnerability, like in the TCP/IP stack? What then? Do you unplug your computer from the internet entirely? Ok, but who got infected first to tell you to do that? Someone had to take one for the team. Either way, damage has been done people.

This is why the practice of stockpiling exploits has to stop. The US government (and others, for that matter) should report exploits, not store them as cyber weapons. As weapons of war, they are as likely to hurt us in the end as our enemies, and that makes them very bad weapons in the perspective of one of the first rules of warfare; Don't hurt your own team.

Call me crazy, but that just seems like a weapon I'd rather not use. If a weapon hurts as many of your own team as your enemy or even close to that number, its time to retire that weapon. Of course, we aren't talking a literal injury or body count here, but the concept is the same. This is just a bad practice, and it needs to stop.

57 Comments on WannaCry: Its Origins, and Why Future Attacks may be Worse

I guess that logic is flawed?You can't ever "protect" something that will eventually be discovered elsewhere. Remember heartbleed? NSA didn't report that one either, and it did not require a leak.Latest chips have a management system, yes. No exploit known yet. But yes.

I've also been against management "security" subsystems since day one, but that's a separate argument.

My point is, you seem to be arguing this behavior is acceptable and good for society. It's not. If your an everyday citizen, my point stands that none of this is any good for you.

The Military takes an oath to protect the constitution. This in turn is supposed to protect its citizens. But, that doesn't mean they wont kill indiscriminately if all of our culture and society is in danger. I know they would do their best to save as many as possible but, if it came down to it they would obliterate a US town or city. Civilians and all to protect the greater good. ALL MILITARIES would. It only makes logistical sense. Let me give you a modern example.

In the 1960's there were riots in Georgia. The local police couldn't get it under control and yeah it was all race related. My father was stationed in Ft. Benning or Ft. Gordon. Not sure which. In the early evening they call got called up to gear up. My old man fresh out of boot camp had no idea what was going on. He thought the US might be under attack. Nope. Not from an invading army but, from internally. They received the orders to take back a suburb of Atlanta. Indiscriminately take the city back. They had live ammo and nothing they carried was non-lethal. That kind of stuff didn't exist in the early 60's. I'm talking full auto M-14's and jeeps with MaDuces. They were to roll out at dawn. Luckily the cops got it under control with dogs and water cannons and the military was called off. The U.S. government feared that the riots would spread and we would have nationwide civil unrest to the point of collapse as the riots were not just localized to Georgia. Things came REAL CLOSE to marshal law. I hope you don't think things are different today because they aint. That town was to be an example to the rest.

Also our largest deterrent is the biggest indiscriminate killer in the history of man. The H-Bomb. We maybe culturally different than the Russians. We tend to fight differently. But, the end goal is always the same. Win at all costs. With that being said how many launch codes have been leaked to the public? Yeah that's what I thought.

The train crashes here, this thread is done.

*shrugs*

You seem to jump over my points to disprove points I don't even try to make.A launch code is different than a stack overflow or similar vulnerability. One is mathematically likely to be found within a 10 year period without any leak. The other is nearly impossible.