Thursday, May 18th 2017

WannaCry: Its Origins, and Why Future Attacks may be Worse

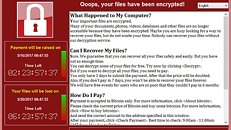

WannaCry, the Cryptographic Ransomware that encrypted entire PCs and then demanded payment via Bitcoin to unlock them, is actually not a new piece of technology. Ransomware of this type has existed nearly as long as the cryptocurrency Bitcoin has. What made headlines was the pace with which it spread and the level of damage it caused to several facilities dependent on old, seldom-updated software (Hospitals, for example). It's not a stretch to say this may be the first cyberattack directly attributable to a civilian death, though that has not been concluded yet as we are still waiting for the dust to settle. What is clear however is WHY it spread so quickly, and it's quite simple really: Many users don't have their PCs up to date.Indeed, the bug that WannaCry utilized to spread this rather old-school ransomware tech had been patched in Windows for about 2 months at the date of the outbreak. But many users were still not patched up. To be clear, this is not just hospital equipment and such that may be difficult to directly patch, but also end user PCs that simply aren't patched due to user ignorance or outright laziness. That as a cultural issue can be fixed relatively easily (and to some degree already is with the push of Windows 10 which handles this automatically for the user). But there is a more sinister twist to this story, one that indicates future outbreaks may be worse. The bug that enabled this to happen was leaked directly from the NSA, and had been known for much much longer than the patch for it has existed. In other words, this bug had been stockpiled by the US government for use in cyberwarfare, and its leak caused this attack.

Let me play you a theoretical scenario, one not so farfetched I would think. What if Microsoft had NOT had a patch ready at the time of this outbreak? What if the bug (which exists in the file sharing stack and has most Windows PC vulnerable by default) was exposed and we had to wait a couple days for a patch. What can you do to protect yourself then?

This seemingly nightmarish scenario is a good illustration of why stockpiling vulnerabilities in common software rather than reporting them is a bad practice rather than a good one. Of course, in the above situation, you could just turn your PC off until it all blows over, or turn off SMB1 file sharing in Windows (google will help you here). Or best yet, you could use a decent firewall setup that does NOT expose SMB ports to the internet (you can even block the ports in Windows Firewall, google again has the answers). But not all of us are power users. Most out there aren't, actually. A lot of users actually plug their computers directly into their modems. I know, because I've worked IT. I've seen it. And what about when someone finds a worse vulnerability, like in the TCP/IP stack? What then? Do you unplug your computer from the internet entirely? Ok, but who got infected first to tell you to do that? Someone had to take one for the team. Either way, damage has been done people.

This is why the practice of stockpiling exploits has to stop. The US government (and others, for that matter) should report exploits, not store them as cyber weapons. As weapons of war, they are as likely to hurt us in the end as our enemies, and that makes them very bad weapons in the perspective of one of the first rules of warfare; Don't hurt your own team.

Call me crazy, but that just seems like a weapon I'd rather not use. If a weapon hurts as many of your own team as your enemy or even close to that number, its time to retire that weapon. Of course, we aren't talking a literal injury or body count here, but the concept is the same. This is just a bad practice, and it needs to stop.

Let me play you a theoretical scenario, one not so farfetched I would think. What if Microsoft had NOT had a patch ready at the time of this outbreak? What if the bug (which exists in the file sharing stack and has most Windows PC vulnerable by default) was exposed and we had to wait a couple days for a patch. What can you do to protect yourself then?

This seemingly nightmarish scenario is a good illustration of why stockpiling vulnerabilities in common software rather than reporting them is a bad practice rather than a good one. Of course, in the above situation, you could just turn your PC off until it all blows over, or turn off SMB1 file sharing in Windows (google will help you here). Or best yet, you could use a decent firewall setup that does NOT expose SMB ports to the internet (you can even block the ports in Windows Firewall, google again has the answers). But not all of us are power users. Most out there aren't, actually. A lot of users actually plug their computers directly into their modems. I know, because I've worked IT. I've seen it. And what about when someone finds a worse vulnerability, like in the TCP/IP stack? What then? Do you unplug your computer from the internet entirely? Ok, but who got infected first to tell you to do that? Someone had to take one for the team. Either way, damage has been done people.

This is why the practice of stockpiling exploits has to stop. The US government (and others, for that matter) should report exploits, not store them as cyber weapons. As weapons of war, they are as likely to hurt us in the end as our enemies, and that makes them very bad weapons in the perspective of one of the first rules of warfare; Don't hurt your own team.

Call me crazy, but that just seems like a weapon I'd rather not use. If a weapon hurts as many of your own team as your enemy or even close to that number, its time to retire that weapon. Of course, we aren't talking a literal injury or body count here, but the concept is the same. This is just a bad practice, and it needs to stop.

57 Comments on WannaCry: Its Origins, and Why Future Attacks may be Worse

That's the issue report. You'll note patches were issued for Windows 10.

If they were up to date on patches it wouldn't matter what av you used, same thing if you don't lock your doors it doesn't matter what security you have. How is that logic flawed? Where did you get dental from?

About IoT: different topic, but here goes: correctly implemented it could be amazing, and in fact it already is pretty great in the right context, such as industry and engines.

Or perhaps Windows 10 ships with a more sensible out of the box firewall config. That could explain it too, I guess.

1. Infect a friend. Get a discount on your ransom if you infect a friend and they pay.

2. Phone numbers directly to bitcoin vendors. (people running insecure systems love phones.)

3. Phone number to tech support company that bills your credit card to walk you through paying the ransom.

4. Delayed symptoms. Secretly encrypt backups (windows efs might be able to do it nonobviously) Then once all your backups are secretly encrypted, it encrypts the key, and now you can't use backups to save yourself.

5. Deterministic wallet stores all profit in a simple 12 word seed "password"

6. Advertise affiliated antivirus (I hear this is what cloudflare does by hosting bad actors, they inflate their demand from protection from bad actors, just a rumor though.)

7. New address per machine (easier to detect payments made, hides profit total.)

8. Lock computer out in addition to encrypting. (Makes it harder for them to buy bitcoin though.)

$2000 bitcoin sure is crazy. Stay safe, Richard Heart on Youtube.

This is quasi cold war methodologies though. I would rather have this then real weapons being used and I think most people would agree.

Having said that, it doesn't mean that there can't be a middle ground. For example, the US government, can and should advise the software / firmware companies of the vulnerability but have a standing agreement that such quasi weaponized vulnerabilities would be patched in a stealthy way only within the US and possibly within regions of its friends and allies. This would only be for a predefined period of time though because nothing lasts forever and therefore the genie will eventually get out of the bottle. American companies shouldn't have too much of an issue with this although clearly some would.

Part of the problem though is that the US likely wanted to use these vulnerabilities not just outside of the US but rather on their own population. That kind of mindset makes such problems an inevitability.

Other nations have rejected Windows on some level due to these issues and you really can't blame them for it.

Buffer overflow attacks are almost par for the course with any lower level language such as C. Cost of entry.Much of what you describe has already happened, just not with this variant.

However, since the Windows 10 update that was released in July of 16', I have disabled updates on my HTPC. Perhaps there will be those in this thread who will jump all over me for that, however, every time I have tried to update my HTPC since July of last year, something has broken that I use and consider essential that it functions every time I use that PC. Before anyone jumps on me for disabling updates, search for things like "Windows 10 black screen" (a particularly nasty one which a co-worker and I experienced) or "Windows 10 update breaks WiFi". Solutions for many of the issues do not exist, and going to Microsoft's support site is almost worthless when the supposed experts almost always respond with inane responses that often amount to "Is your computer on?"

Everyone may not realize this, however, Windows 10 updates are riddled with bugs some of which are serious enough to make a PC completely unusable, and it appears to be random as to whether or not your particular configuration of hardware and software will be impacted when a 10 update is applied. I simply do not want to spend the time to test an update, and ensure that it works when I apply it. That is supposed to be the job of Microsoft. Fortunately, I disk image before I attempt an update, so reverting is not that much of a time consumer; however, the update itself usually is a big time consumer.

So there is a tough choice here. Apply a 10 update, and potentially end up with a computer that is completely unusable, or apply the update and be safe from potential vulnerabilities if you are lucky enough not to encounter a bug in the update that breaks the PC.

To me, if an Update renders a PC unusable, then the update is much worse than a virus. I started with Win 3.1, and as I see it, 10 updates have been as bad as NT updates which could almost always be counted on to blue screen any PC on which they were installed. As I see it, Microsoft needs to stop pushing out Windows 10 updates that break either the entire computer or any subsystem that may be in use.

If Microsoft had wanted to, they could have their own people testing all the OS releases for vulnerabilities, and, as I see it (since they did not) they now want to pass the buck to the NSA for the release of this vulnerability. I realize that testing is expensive, but one thing that I don't think anyone in their right mind will argue is that with Big Bill's Billions, vulnerability testing would have been a drop in the bucket to his bank account.

As I see it, Microsoft should be doing a better job with update testing and vulnerability testing, and they have no excuse for the lackadaisical job they are currently doing with each.

Do NOT post your full IP here, but you can post the first two numbers pretty safely (the first two numbers might give out your location (country) or service provider, if you're worried, don't post any of it.)

My original ADSL modem (years ago) used to be plugged in the USB port of the PC, never used it, bought a Netgear Modem/router instead ;) and configured it to work.

Also the logic of this editorial is flawed. As long as defence systems are not effected, security agencies will ALWAYS stockpile. Think about our nuclear arsenal. Difference is they didn't protect it like the should have. They need to stop scouring this stuff out to contractors and keep it at a military level like we do our nukes. If they did, this wouldn't have happened.