Tuesday, June 26th 2018

On The Coming Chiplet Revolution and AMD's MCM Promise

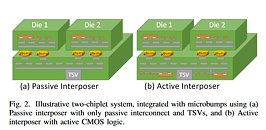

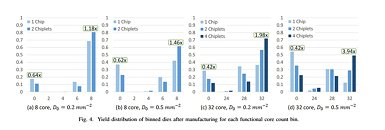

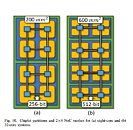

With Moore's Law being pronounced as within its death throes, historic monolithic die designs are becoming increasingly expensive to manufacture. It's no secret that both AMD and NVIDIA have been exploring an MCM (Multi-Chip-Module) approach towards diverting from monolithic die designs over to a much more manageable, "chiplet" design. Essentially, AMD has achieved this in different ways with its Zen line of CPUs (two CPU modules of four cores each linked via the company's Infinity Fabric interconnect), and their own R9 and Vega graphics cards, which take another approach in packaging memory and the graphics processing die in the same silicon base - an interposer.This "chiplet" approach is easy to understand - smaller, leaner chips can be produced with higher yields than large, monolithic ones, which are more prone to silicon defects. This increased yield (and increased number of chips per wafer, in the end) allows AMD to reduce manufacturing costs and increase production efficiency by using a single mask for a quad-core module, for instance. Afterwards, it's "simply" a matter of scaling the number of modules to the desired amount and performance paradigm - from eight-core Ryzen CPUs to 32-core Threadripper II CPUs. However, as the number of modules in a given chip increase, so does complexity of signal processing and routing - two modules communicating with each other is relatively easy to achieve, but six or eight modules? Not so much, as a small hiccup in information transmission can deadlock the entire processor (speaking of either CPU or GPU designs here now). The challenge becomes increasingly greater when joining different types of chips - from memory to processing dies and I/O controllers - in a single silicon slice. This is where interposers appear - and where AMD is taking strides towards achieving an active interposer design.Passive interposers - such as the one found in the AMD Vega graphics cards - are simply a "dumb", silicon-enabler of data transmission - information is sent exactly as it was engineered to with the TSV (Through Silicon Vias) design. However, this approach is insufficient in the dream, open approach to chip integration - where manufacturers can create their designs, purchase other chips from other companies, and mix and match according to their end-product requirement. A "dumb", passive interposer won't suffice here - data routing problems would have to be manually solved with each different implementation, which is prohibitive from the cost perspective, and a big no-no for the approach. The solution, as AMD puts it on their "Cost-Effective Design of Scalable High-Performance Systems Using Active and Passive Interposers" paper, can be found, at least partially, with an active interposer - an interposer that features network logic (NoC - Network on Chip) that can adapt to the different slices of silicon grafted onto it. And this isn't just theoretics - active interposer designs have been manufactured, showing "improved signaling and efficiency over passive interposer [design]).

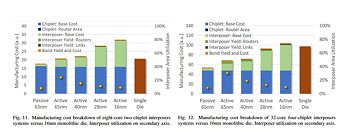

A big problem for this active interposer approach, however, is cost - again, the end of many promising technologies. AMD, however, is actively working on building enough redundancy in the active interposer design that yields aren't much of a concern - achieving the sweetspot between development cost and yield ratio. Nothing is worse than paying for a big-area, active interposer die with all of its network circuitry and have it have such defects that it can't be used.For now, AMD says these active interposers ought to be reserved for high-performance designs - not surprising, given the added R&D cost over passive interposer or sans-interposer design. The dream to mix and match and reuse different IPs at will via a "simple" substrate, however, is very much alive. AMD researchers proved that for 32-core processors - with possibilities of scaling with estimated monolithic die complexity versus the chiplet approach - could be achieved with much better yield and lower manufacturing cost in the chiplet + passive /active interposer design versus a monolithic 16 nm die.The process used to fabricate the interposer is very important here - so as to increase yield ratios, 65 nm through 28 nm active or passive solutions provide reduced development and manufacturing costs. Active interposers, while more expensive than their passive counterparts, add the aforementioned networking capabilities that allow for zero deadlock possibility, routing signals as needed between different components of the design.

Sources:

Cost-Effective Design of Scalable High-Performance Systems Using Active and Passive Interposers, Via IEEE

A big problem for this active interposer approach, however, is cost - again, the end of many promising technologies. AMD, however, is actively working on building enough redundancy in the active interposer design that yields aren't much of a concern - achieving the sweetspot between development cost and yield ratio. Nothing is worse than paying for a big-area, active interposer die with all of its network circuitry and have it have such defects that it can't be used.For now, AMD says these active interposers ought to be reserved for high-performance designs - not surprising, given the added R&D cost over passive interposer or sans-interposer design. The dream to mix and match and reuse different IPs at will via a "simple" substrate, however, is very much alive. AMD researchers proved that for 32-core processors - with possibilities of scaling with estimated monolithic die complexity versus the chiplet approach - could be achieved with much better yield and lower manufacturing cost in the chiplet + passive /active interposer design versus a monolithic 16 nm die.The process used to fabricate the interposer is very important here - so as to increase yield ratios, 65 nm through 28 nm active or passive solutions provide reduced development and manufacturing costs. Active interposers, while more expensive than their passive counterparts, add the aforementioned networking capabilities that allow for zero deadlock possibility, routing signals as needed between different components of the design.

17 Comments on On The Coming Chiplet Revolution and AMD's MCM Promise

A silicon interposer is little different ,an active one makes this a 3d soc imho and a first.

Emib on the other hand is on chip fully, afaik it requires chips to conform with each other though a tsv version and 2.5d i suppose do make sense ,i might be wrong their i have not heard of anything bar chip to chip though, possibly better being so direct , maybe that's why Amd mentioned active to counter EMIB.

I appreciate the update, but as I heard MCM for GPU is far from ready for primetime.

It's one of the better articles on TPU I have read. We need more of this type of stuff, just this.

An interposer only makes sense when you have a wast amount of wiring and not enough space to route them through a substrate.

MCM GPUs (made up of multiple GPU dies) won't work unless they're abstract to the host as one GPU (multi-GPU is dead), even then I can't begin to imagine the software side chaos of distributing workload between GPU dies while pretending that they make up one GPU (and not multi-GPU). Unless of course that MCM GPUs are being targeted at HPC/AI and not gamers.

EMIB resolves the problem with interposer size. Patents and implementation details will undoubtedly be an interesting fight we will see soon enough.Infinity Fabric seems to have received more hype than it's worth. It is definitely awesome but it is not the only contemporary scalable interconnect out there.

AMD has Infinity Fabric:

AMD has stated the range to be 30 GB/s to 512 GB/s. Implementation details seem to be somewhat different depending on type of interconnect - in Zen's case inside (2x32 bits) or between chips (2x16 wires).

Actual implementation: In EPIC/TR/Ryzen each link inside chip has bandwidth 42 GB/s bi-directionally and between chips 38 GB/s bi-directionally. This is with the spec DDR4-2666 memory and 1333 MHz clock.

Nvidia has NVLink:

A channel (link) is 32 wires - 8-bit differential pairs (lanes) and bi-directional. 20 GT/s (or 25 for NVLink 2.0). Assuming NVLink 2.0, that is 25GB/s per link, 50GB/s bi-directional and can be scaled up with more links. NVLink's NVSwitch is 18-port and total bandwidth of 900 GB/s so NVLink by itself does seem to be scalable.

Actual implementation: Big Pascal has 4 NVLink 1.0 links - 80/160 GB/s, big Volta has 6 NVLink 2.0 links - 150/300 GB/s.

Intel has QPI (and soon UPI):

These are Intel's multi-CPU interconnects that have been evolving over time. Historically these tend to favor latency over bandwidth as that has been Intel's need. Currently, dual-socket Xeon systems actually have inter-CPU latencies that are nor far off from inter-chip IF in EPIC CPUs. As an interesting note, QPI is 20-lane link (40 data wires) logically divided into 4 quadrants, 5 lane each. These quadrants can be managed separately.

UPI is stated to have 10.4 GT/s and 2-3 UPI links per CPU which brings some management and power improvements but performance-wise is just the same interconnect as QPI running at max 5.2 GHz.

Actual Implementation: Initial implementation in Nehalem was running at 3.2 Ghz with resulting bandwidth of 25.6 GB/s. Haswell's implementation is running at 4.8 GHz and bandwidth 38.4 GB/s.

UPI will bring the bandwidth per link up to 41.6 GB/s.

This is just bandwidth. There are several other important considerations. Latency is one, power consumption is another, die space consumed becomes a problem at some amount of links as well.I think power is the primary consideration here. Powering the links on/through interposer conserves power when compared to links on/though PCB.

AMD has declared power efficiency as one of the wins of Infinity Fabric and it does consume a notable amount of power in TR/EPIC. Intel, in the same manner, is trying to reduce the power consumption going from QPI to UPI.The problem is not the link as much as managing traffic on a bunch of high-speed links. Interconnect itself will still be Infinity Fabric but the active part on the interposer will have to be a switch of some type.

But this is still a physical(ish) layer problem, software issues are on top of all this.3dfx's approach to multiple chips was SLI (Scan-Line Interleave) that was employed on both multiple chips on Voodoo 4/5 cards as well as linking two separate Voodoo2 cards. Then, each chip simply rendered the next row of pixels. While the specific method has not been used for a long time, this type of work distribution is easily doable by both AMD and Nvidia today with Crossfire and SLI respectively. Unfortunately, GPU functionality as well as engines have become much more complex so these naive methods are too twitchy. Interconnect is not the problem here unless using a brute force method of using an extremely wide and low latency bus which is technically not viable.

AMD's GPU chief has now confirmed that Navi will not be an MCM approach and while they would like to (and most definitely do) explore this, it is not in the cards in foreseeable future.

While I understand the article and it is good... while more technical for most, the only issue I kind of was looking to point out is this is still in a "theory stage" for GPU's. Even with interposer they have many huddles.btarunr; as above basically offers the same issue I tried to add that wasn't explicit in the article. That was, the biggest evolution that needs to start working itself out and always the Achilles Heel of ground breaking technology have special individual competing technologies. Worst is as londiste post covers, everyone is in the throes of their competing implementations, with the hope all these implementations would come about so that each' companies implementation is imperceptible to greater use of outside software, drivers etc.

An actually smart interposer is like having trafic lights instead of a single lane for all cars. It's potentially a very huge improvement to throughput, so I can't see how you can say "interconnect speed needs a much more speedy/robust cross-talk that as of yet Infinity Fabric has not (yet) provided" because you "heard" that "MCM for GPU is far from ready for primetime". This article literally and directly addresses the cross-talk problem and offers a new solution. Your comment makes no sense at all in light of this not being Infinity Fabric as it is right now, like it seems you're saying.

www.pcgamesn.com/amd-navi-monolithic-gpu-design

www.tweaktown.com/news/62244/amd-ready-mcm-radeon-skip-navi-gpu-arch/index.html

I just saw this as "tantalizing" and more put-out there by AMD to deflect those earlier stories that MCM had hurdles, while help to displace what Raja Koduri had said about Vega a while back, that the Infinity Fabric interconnect would be the "perfect system" to splice a bunch of discrete GPUs together on a single ASIC design.

Then I don't find in the article talking about "traffic signal", best I read was improved signaling and efficiency over passive interposer. While at some point AMD can probably make this work as can others there are plenty of hurdles.

EMIB - Passive Silicon Bridge

Next should be Active Silicon Interposer and active Silicon Bridge